*

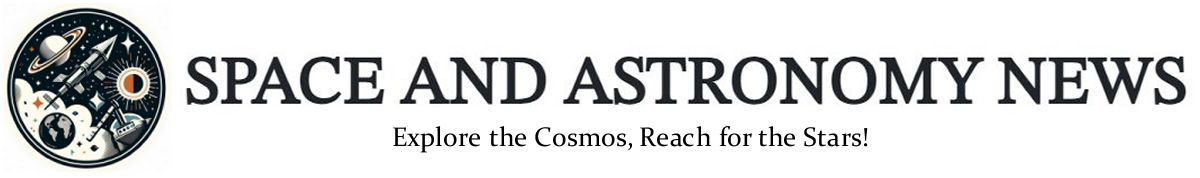

In a few billion years, our Sun will die. It will first enter a red giant stage, swelling in size to perhaps the orbit of Earth. Its outer layers will be cast off into space, while its core settles to become a white dwarf. Life on Earth will boil away, and our planet itself might be consumed by the Sun. White dwarfs are the fate of all midsize stars, and given the path of their demise, it seems reasonable to assume that any planets die with their sun. But the fate of white dwarf planets may not be lifeless after all.

More than a dozen planets have been discovered orbiting white dwarf stars. That’s a small fraction of the known exoplanets, but it tells us that planets can survive the red giant stage of a Sun-like star. Some planets may be consumed, and the orbits of survivors might be dramatically affected, but some planets retain a stable orbit. Any planets that were in the habitable zone of the star would die off, but a new study suggests that some white dwarf planets might give life the foothold it needs to evolve again.

Although white dwarfs don’t undergo nuclear fusion, they do remain warm for billions of years. Young white dwarfs can have a surface temperature of 27,000 K or more, and it takes billions of years for them to cool. Since the simple definition of a star’s habitable zone is simply the range where a planet is warm enough for liquid water, this means all white dwarfs have a habitable zone. Unlike main sequence stars, however, this region would migrate inward as the star cools. But in this new work, the authors show that white dwarfs have a habitable zone that would be warm enough for life across billions of years. For a white dwarf of about 60% of the Sun’s mass, part of the habitable zone would persist for nearly 7 billion years, which is more than enough time for life to evolve and thrive on a world. In comparison, the Earth is less than 5 billion years old.

Of course, for life to appear on a white dwarf planet, simply being warm isn’t enough. To have the kind of complex life we see on Earth, the spectrum of starlight would need to provide the right kind of energy for things like photosynthesis without ionizing the planet’s atmosphere. The spectra of white dwarfs are shifted much more to the ultraviolet than the visible and infrared, but the authors show that ionizing radiation would not be severe, and the amount of UV would allow for Earth-like photosynthesis. The optimal habitable zone would be close to the white dwarf, similar to the habitable zone of the TRAPPIST-1 red dwarf.

Just because a white dwarf planet might be home to life, that doesn’t mean they are. We know life can exist around a Sun-like star, but we’d need clear evidence to say the same is true for white dwarfs. That’s where the second part of this work comes in. Since white dwarfs are bright for their size and habitable planets would need to orbit them closely, our ability to gather evidence on them is good. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), for example, is sensitive enough to observe the atmospheric spectra of white dwarf planets as they transit. A few hours of observational time could be enough to get a spectrum sharp enough to detect biosignatures.

All that said, finding life on a white dwarf planet is a long shot. The planets would likely have to migrate inward during the latter part of the red dwarf stage, maintain a stable orbit, and somehow retain or recapture the kind of water-rich atmosphere you need for terrestrial life. That’s a big ask. But given how easy it might be to detect biosignatures, it’s worth taking a look.

Reference: Whyte, Caldon T., et al. “Potential for life to exist and be detected on Earth-like planets orbiting white dwarfs.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.18934 (2024)