[ad_1]

- Astronomers are getting better at spotting asteroids that could potentially collide with Earth.

- We’ve now spotted nine asteroids before impact with Earth’s atmosphere. The most recent space rock spotted before it struck burned in the atmosphere up above the Philippines on September 5, 2024.

- By identifying hazardous asteroids sooner, we have a better chance to mitigate potential impacts and reduce the risk of a catastrophe.

By Daniel Brown, Nottingham Trent University

Astronomers are getting better at spotting asteroids

On September 4, 2024, astronomers discovered an asteroid, 3 feet (1 m) in diameter, heading toward Earth. The space rock burned up harmlessly in the atmosphere near the Philippines later that day, officials announced. Nevertheless, it produced a spectacular fireball that people shared in videos posted on social media.

The object, known as RW1, was only the ninth asteroid to be spotted before impact. But what of much bigger, more dangerous asteroids? Would our warning systems be able to detect all the asteroids that are capable of threatening us on the ground?

Asteroid impacts have influenced every large body in the solar system. They shape their appearance, alter their chemical abundance and – in the case of our own planet at the very least – they helped kickstart the formation of life. But these same events can also disrupt ecosystems, wiping out life, as they did 66 million years ago when a 6-mile (10-km) space rock contributed to the extinction of the dinosaurs (excluding birds).

What are asteroids?

Asteroids are the material left over from the formation of our solar system that did not become part of planets and moons. Asteroids come in all shapes and sizes. Gravity determines their paths and they can, to some extent, be predicted. Of particular interest are the objects that are close to Earth’s orbit called near-Earth objects (NEOs). As of September 2024, we know of approximately 36,000 such objects, ranging in size from several meters to a few kilometers.

But statistical models predict nearly 1 billion such objects should exist. And we only know of very few of them.

Monitoring asteroids

We have been monitoring these asteroids since the 1980s and setting up more detailed surveys of them since the 1990s. The surveys use telescopes to make observations of the entire sky every night. Then they compare images of the same region on different dates.

Astronomers are interested in whether, in the same area of the sky, something has moved with respect to the stars from one night to another. Anything that has moved could be an asteroid. Observing its positions over a longer period allows team members to determine its exact path. This, in turn, enables them to predict where it will be in future, though such data collection and analysis is a time-consuming process that requires patience.

It is made even more challenging by the fact that there are many more smaller objects out there than bigger ones. Some of these smaller objects are nevertheless of sufficient size to cause damage on Earth, so we still need to monitor them. They are also faint and therefore harder to see with telescopes.

It can be difficult to predict the paths of smaller objects long into the future. This is because they have gravitational interactions with all the other objects in the solar system. Even a small gravitational pull on a smaller object can, over time, alter its future orbit in unpredictable ways.

More help to find the next killer asteroid

Funding is crucial in this effort to detect dangerous asteroids and predict their paths. In 2023, NASA allocated US$90 million (£68 million) to hunt for near Earth objects (NEOs). There are several missions in development to detect hazardous objects from space. Examples include the Sutter Ultra project and NASA’s NEOsurveyor infrared telescope mission.

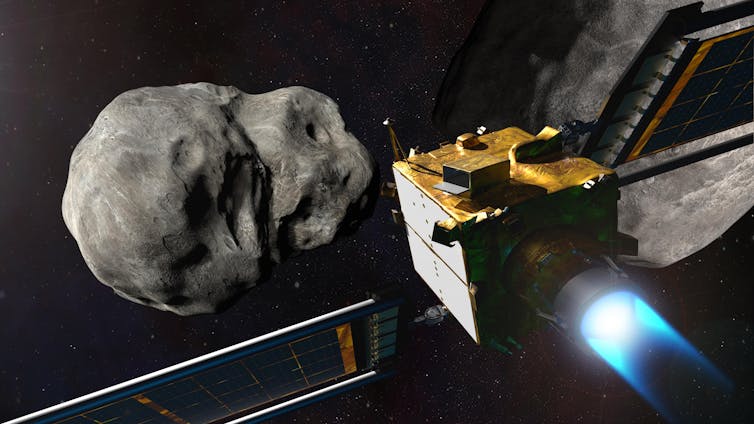

There are even space missions to explore realistic scenarios for altering the paths of asteroids such as the DART mission. DART crashed into an asteroid’s moon so scientists could measure the changes in its path. DART showed it was possible in principle to alter the course of an asteroid by crashing a spacecraft into it. But we’re still far from a concrete solution that could be used in the event of a large asteroid that was really threatening Earth.

Detection programs create a huge amount of image data every day, which is challenging for astronomers to work through quickly. However, AI could help: advanced algorithms could automate the process to a greater degree. Citizen science projects can also open up the task of sorting through the data to the public.

Our current efforts are working, as demonstrated by the detection of the relatively small asteroid RW1. Astronomers only discovered it briefly before it struck Earth. But it gives us hope that we are on the right track.

Bigger asteroids mean greater destruction

Asteroids less than 80 feet (25 meters) in diameter generally burn up before they can cause any damage. But objects of 80 to 3,300 feet (25 to 1,000 meters) in diameter are large enough to get through our atmosphere and cause localized damage. The extent of this damage depends upon the properties of the object and the area where it will hit. But an asteroid of 460 feet (140 meters) in size could cause widespread destruction if it hit a city.

Luckily, collisions with asteroids in this size range are less frequent than for smaller objects. A 460-foot (140-meter) diameter object should hit Earth every 2,000 years.

As of 2023, statistical models suggest we know of 38% of all existing near Earth objects with a size of 460 feet (140 meters) or larger. With the new Vera Rubin 8.5-meter telescope, we hope to increase this fraction to roughly 60% by 2025. NASA’s NEOsurveyor infrared telescope could identify 76% of asteroids 460 feet (140 meters) in size or bigger by 2027.

Asteroids larger than 1 kilometer in size have the ability to cause damage on a global scale, similar to the one that helped to wipe out the dinosaurs. These asteroids are much rarer but easier to spot. Since 2011, we think we have detected 93% of these objects.

After detection, then what?

Less comforting is the fact that we have no current realistic proposal for diverting its path, though missions like DART are a start. We might eventually be able to compile a near-complete list of all possible asteroids that could cause global impacts on Earth.

It’s much less likely that we will ever detect every object that could cause localized damage on Earth, such as destroying a city. We can only continue to monitor what’s out there, creating a warning system that will allow us to prepare and react.![]()

Daniel Brown, Lecturer in Astronomy, Nottingham Trent University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Astronomers are getting better at spotting asteroids, such as the asteroid that hit Earth near the Philippines on September 5, 2024. New observatories will help spot more asteroids. But what happens after we spot them?

[ad_2]

Source link

No comments! Be the first commenter?