[ad_1]

Terry Lovejoy

We’re all hungry for news about C/2023 A3 Tsuchinshan-ATLAS. Well, I’ve got some. First, Australian amateur astronomer and six-time comet discoverer Terry Lovejoy posted the first ground-based photo of C/2023 A3 since it was overcome by solar glare in mid-August. Until Lovejoy corralled it on September 11.8 Universal Time, the comet was only accessible remotely by orbiting spacecraft.

Lovejoy recovered the comet in Sextans just 14° from the Sun in bright morning twilight at magnitude 5.5. The photo shows that the Oort Cloud visitor is still intact with a bright, compact coma and a faint, feather-shaped tail extending to the upper right (southwest). The comet’s solar elongation is increasing at the moment, so we should see more images and observations from Southern Hemisphere observers soon. Comet-lovers at 40° north will get their first crack at it on or about September 23rd.

The other good news comes to us from the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams which issues timely astronomical news flashes called CBETs (Central Bureau Electronic Telegrams). In CBET #5445, posted on September 10, comet researcher Joseph Marcus predicts strong forward-scattering enhancement of the comet’s light around the time it reaches its greatest phase angle, which will occur on October 9th.

Bob King

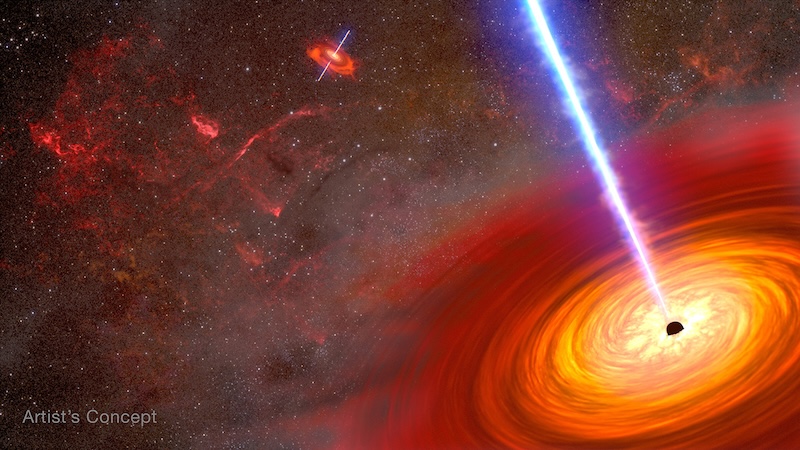

Left: Nathanael Callon, public domain; Right: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Observations indicate that C/2023 A3 appears to be a particularly dusty comet based on the structure and form of its tail and the fact that the nucleus has produced far more dust than diatomic carbon (C2) emissions, the gas that gives so many comets their radiant green hue.

Marcus cautiously predicts the following magnitudes and phase angles (he gives scattering angles; I converted them to phase angles):

| Date | Phase angle | Visual magnitude |

| Sept. 29.0 UT | 100.5° | –0.3 |

| Oct. 2.0 | 121.3° | –1.1 |

| Oct. 5.0 | 143.3° | –2.5 |

| Oct. 6.0 | 150.9° | –3.2 |

| Oct. 7.0 | 158.6° | –4.1 |

| Oct. 8.0 | 166.1° | –5.3 |

| Oct. 9.0 | 172.1° | –6.7 |

| Oct. 9.4 | 173.0° | –6.9 |

| Oct. 10.0 | 171.5° | –6.5 |

| Oct. 11.0 | 164.9° | –5.1 |

| Oct. 12.0 | 157.0° | –3.9 |

| Oct. 13.0 | 148.9° | –3.0 |

| Oct. 14.0 | 140.9° | –2.3 |

| Oct. 15.0 | 133.2° | –1.7 |

| Oct. 18.0 | 112.9° | –0.7 |

| Oct. 21.0 | 96.9° | –0.2 |

Taken together, the comet’s dustiness, phase angle, and efficient forward-scattering all point to it potentially becoming visible during daylight. These factors also mean a brighter appearance at twilight, when the comet will best be visible during the upcoming apparition. For instance, on October 12th, about the time it first appears in the evening sky for northern hemisphere observers, C/2023 A3 could reach magnitude –4 and put on a spectacular show reminiscent of Comet McNaught (C/2006 P1).

Stellarium

Jan Mark Vornhusen, CC BY-SA 3.0

Like Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, forward-scattering due to a high phase angle (149° at peak on Jan. 14, 2007) played a significant role in boosting McNaught’s brightness. Can we expect a similar performance from C/2023 A3? Yes and no. Marcus is confident in the forward-scattering model because it’s been tested and proven in observations of earlier comets.

“What I am less confident about is the comet’s baseline brightness forecast,” he wrote in an email.

We still don’t know the intrinsic brightness of Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS since solar glare has essentially curtailed observations since early August — more than a month before its September 27th perihelion. Lacking that data, visual magnitude predictions “could easily be off one or two magnitudes in either direction by the time we get to October,” said Marcus. Hopefully, Lovejoy’s recovery will spur more observations to help refine that value.

S. Deiries / ESO

Another reason C/2023 A3 may not necessarily be a repeat of Comet McNaught — despite the favorable forward-scattering situation — relates to its close pass by the Sun. C/2006 P1 experienced more intense heating, and therefore dust release, than C/2023 did, because its perihelion passage brought it much closer to the Sun. (Comet McNaught passed 25.4 million kilometers, or 15.8 million miles, from the Sun versus 58.3 million for Comet Tsuchinshan-ATLAS).

Comets will always be iffy, but I like the new forecast. Like most amateur astronomers, I’m an optimist, so fresh information and images only heightens my anticipation.

[ad_2]

Source link

No comments! Be the first commenter?