CNSA

The Moon rocks returned by Apollo astronauts gave us our first hands-on evidence of lunar volcanism, showing it to be ancient — dating back to at least 3.1 billion years ago. Yet there have been claims of more recent activity, based on orbital sensing and ground-based imaging, and now new evidence suggests those claims may have been on the right track: The Moon might have had active volcanoes up until relatively recently.

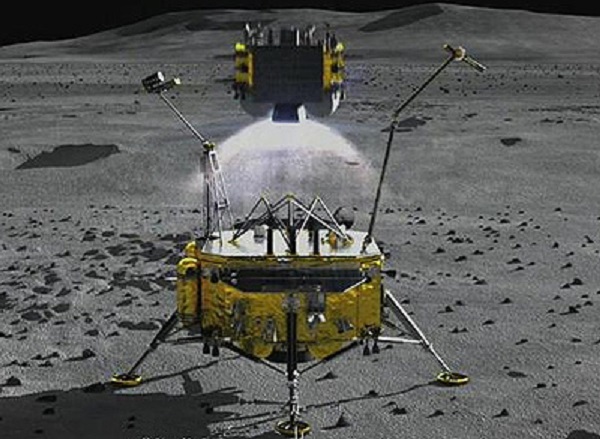

In 2020, the Chinese Chang’e 5 mission returned lunar samples for the first time since the Apollo and Soviet missions of the 1970s. Initial studies showed evidence of volcanic activity as recently as 2 billion years ago. Now, analysis of tiny glass beads in those samples show that active volcanism persisted on the Moon much longer than that. In fact, they point to volcanism occurring just 123 million (give or take 15 million) years ago. In geological terms, that’s almost into the present day.

“We’re going from 2 billion years being the youngest samples that we have in hand, to now materials that are less than a tenth of that age,” says John Delano (State University of New York, Albany), who spent much of his career analyzing the Apollo lunar samples. “That’s a dramatic change in age.”

Because of his expertise with the Apollo samples Delano was recruited by the Chinese team, led by Bi-Wen Wang and Qian Zhang, as their U.S. collaborator to help analyze vast amounts of data collected from 3,000 glass beads recovered from the Chang’e 5 samples of lunar regolith.

In the years since the samples came back, Delano says, the Chinese team has “done this real backbreaking, clever, highly skilled work, including mounting, polishing, and analyzing each bead with a variety of state-of-the-art instruments. He then helped the team use chemical, physical, and isotopic data to home in on 13 interesting beads that show signs of originating in volcanic processes rather than impacts. The Chinese team then “went to town” on those 13, Delano says, narrowing them down to three that contained evidence of surprisingly recent volcanism.

T. Zhang & Y. Wang

“The sulfur isotopes really were the clincher,” Delano says. Different isotopes of a given element contain different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei and respond slightly differently to extreme heating events, whether such an event is a volcanic eruption or a meteor impact. As material melts and vaporizes, lighter isotopes more readily float away from the Moon’s low gravity, leaving more of the heavier isotopes behind.

When vaporized material resolidifies, the ratios of isotopes of different elements can help trace its heating history. While both impacts and volcanic eruptions can produce extreme heating, impacts do so in a much more rapid and non-uniform way, leaving isotopic variations within a sample. Volcanism, on the other hand, produces more uniform heating and little variation, and that’s what the team found in three of the glass beads. Meanwhile, other isotopic ratios in the same sample provide a reliable estimate of the sample’s age.

“The confidence is now high,” Delano says, that these three beads really are signs of relatively recent volcanic activity.

Previous Hints of Present-Day Volcanism

Although there hasn’t been hard evidence before, there have previously been a number of suggestions of recent volcanism based on indirect methods. For example, orbital imagery of the surface suggested volcanism might have occurred in some regions as recently as 70 million years ago, according to a study by Sarah Braden (Arizona State University) and others in 2014. And visual observations of potential volcanic activity, dubbed transient lunar phenomena (TLP), have been reported for centuries, going as far back as Christiaan Huygens in the 1600s — some have even seen apparent plumes of dust. But whether any of these lines of evidence really reflected recent volcanism remained controversial.

In fact, the Chang’e 5 samples were collected “only a couple of hundred miles from some of the most active TLP areas,” Delano says. “That may be a coincidence, but maybe it isn’t.” Indeed, Chang’e 5 grabbed samples from a surface known to be younger than those sampled during the Apollo missions.

CNSA / CLEP / Don Davis

These findings of recent volcanism “suggest there’s a level of activity in the moon that is beyond what current modeling is assuming,” he says. Geophysicists will need to adjust their ideas to account for this, he says.

The Moon: Geologically Alive?

Benjamin Weiss (MIT), a specialist in the formation and evolution of planetary bodies who was not involved in this latest work, says that the evidence presented here is largely statistical. That is, the team combed through thousands of variations of elemental and isotopic compositions to find some whose ratios differed enough from the others to be statistically significant. The finding of three glass beads with such differences would be strengthened by finding additional samples with similar compositions. In fact, the methods used to analyze these glass beads could now be applied to the much more abundant Apollo samples as well, Delano suggests.

“If it’s true, then it’s a really interesting discovery,” Weiss adds. “This would be by far the youngest volcanic melts produced by interior processes on the Moon. It would suggest that the Moon has been volcanically active essentially yesterday.”

The new findings are “part of this growing awareness that maybe the Moon had this longer and more protracted history of geologic activity,” he says.

“The paradigm that we often view the Moon as is this kind of window into the early stages of planetary formation and evolution,” Weiss notes. “So, it’s interesting to consider the idea that this thing that seems like a dead body is continuing to be active.” Because of their continuing sampling of previously unexplored parts of the lunar surface, he says, “the Chinese sample return missions are in the process of sort of revolutionizing our understanding of the recent history of the Moon.”

No comments! Be the first commenter?