*

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27

■ This is the time of year when the rich Cygnus Milky Way crosses the zenith about an hour after full dark (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes). The Milky Way extends straight up from the south-southwest horizon, passes overhead, and runs straight down to the north-northeast.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 28

■ Cygnus itself floats, swan-like, nearly straight overhead these evenings. Its brightest stars form the big Northern Cross. When you face southwest and crane your head way, way up, the cross appears to stand upright. It’s about two fists at arm’s length tall, with Deneb as its top. Or to put it another way, when you face southwest the Swan appears to be diving straight down along the Milky Way.

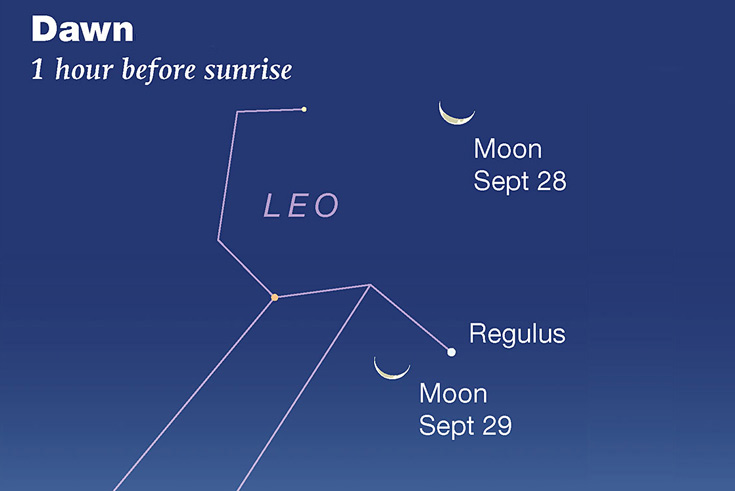

■ Step out before or during early dawn on Sunday morning the 29th, and look for 1st-magnitude Regulus 2° or 3° to the right of the waning crescent Moon, as shown below.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29

■ Face south and look high these evenings after dark. The brightest star there is Altair, the southernmost point of the Summer Triangle. The other two are Deneb and Vega more nearly overhead. A marker for Altair is always its little neighbor Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae), currently a finger-width at arm’s length to Altair’s upper right.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 30

■ The starry W of Cassiopeia stands high in the northeast after dark. The right-hand side of the W (the brightest side) tilts up.

Look at the second segment of the W counting down from the top. It’s not quite horizontal. Notice the dim naked-eye stars along that segment (not counting its two ends). The brightest of these, on the right, is Eta Cassiopeiae, magnitude 3.4. It’s a remarkably Sun-like star just 19 light-years away. But unlike the Sun it has an orange-dwarf companion, magnitude 7.3, separation 13 arcseconds — making it a lovely binary in a telescope.

Left of Eta, and quite a bit fainter, is a naked-eye pair in a dark sky: Upsilon1 and Upsilon2 Cassiopeiae, 0.3° apart, magnitudes 4.8 and 4.6. They’re yellow-orange giants unrelated to each other, 200 and 400 light-years distant from us. Upsilon2 is slightly the brighter of the pair. It’s also the closer one.

TUESDAY, OCTOBER 1

■ Vega is the brightest star barely west of overhead after dark. To its right when you face west and look up, by 14° (nearly a fist and a half at arm’s length), you’ll find Eltanin, the nose of Draco the Dragon. The rest of Draco’s fainter, lozenge-shaped head is a little farther behind. Draco always eyes Vega as they wheel around the sky. In the other direction, his long, arched back and tail loop around the Little Dipper.

The main stars of Vega’s own constellation, Lyra — faint by comparison — extend from Vega in the opposite direction, by half as far as the distance from Vega to Eltanin.

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2

■ One of the brightest very red stars in the sky for binoculars is the carbon star TX Piscium. It’s in the eastern edge of the Circlet of Pisces, which is a little south (lower right) of the Great Square of Pegasus. TX Psc is 5th magnitude visually, in easy binocular range. Carbon stars are unusually red partly because we see them through a red filter: molecular C2 vapor in their atmospheres.

“Less than 2° southwest of TX Piscium is a charming little asterism in the shape of a slanted cross,” writes Matt Wedel in his Binocular Highlight column in the October Sky & Telescope. It’s 2° in length, and its stars range from magnitude 5.6 to 6.5. A fainter, 6.9-magnitude star dimly marks the cross’s center. See Wedel’s chart on page 43 of that issue.

Once you find the TX Cross, you’ll can recognize it in the field of TX Piscium forever after.

■ New Moon today (exact at 2:49 p.m. EDT).

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 3

■ Globular clusters are their most abundant on summer evenings. Now in this first week of October, with the night sky still moonless, set up your telescope to look in on four remaining ones that Josh Urban calls The Last Wildflowers: Globular Clusters Greet Autumn. There’s “Sagittifolia,” the Arrowhead Flower, M71 next to Sagitta; “Queen Anne’s Lace,” M15 sneezed from the nose of Pegasus; “Watercress by the Stream,” M2 in Aquarius a little farther south; and “Seaflower of the Deep,” M30 deep in southern Capricornus.

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 4

■ The Great Square of Pegasus balances on one corner high in the east through much of the evening. Two fists at arm’s length to the Square’s lower right shines Saturn, somewhat brighter.

Extending away from the Great Square’s left corner is the main line of Andromeda, three 2nd-magnitude stars about as bright as those of the Square and spaced similarly far apart. (The three include the Square’s corner itself.) This whole dipper-shaped pattern was named the Andromegasus Dipper by the late Sky & Telescope columnist George Lovi — joining the legendary Big and Little Dippers, the Milk Dipper of Sagittarius (nowadays usually subsumed into the Teapot), and the tiny dipper pattern of the Pleiades.

Venus is plotted here at its position on October 5th (for North America), when it’s 0.9° lower left of Alpha Librae, magnitude 2.8, and the Moon is nearby. Every day Venus moves 1.3° farther to the upper left with respect to the star. You’ll definitely need optical aid for this; Alpha Lib is only 1/500 as bright as Venus!

SATURDAY, OCTOBER 5

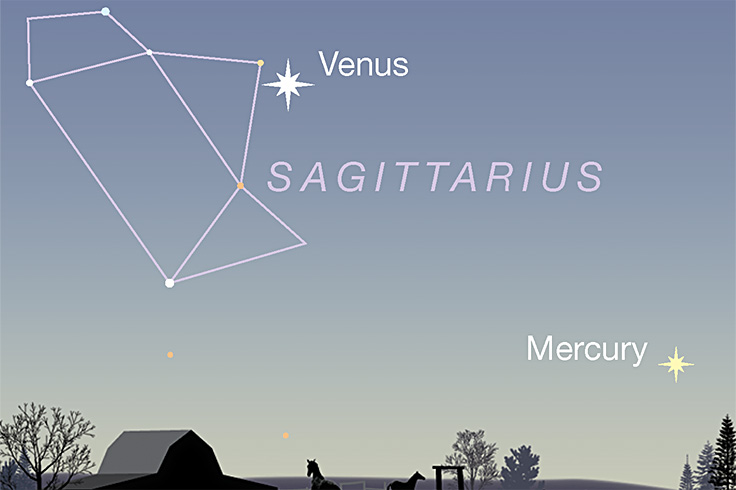

■ About a half hour after sunset, find the thin waxing crescent Moon paired with Venus very low in the southwest as shown above. They’re about 4° apart. A much harder catch is faint Alpha Librae, just under 1° to Venus’s upper right this evening.

SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6

■ After dark look just above the northeast horizon — far below high Cassiopeia — for bright Capella on the rise. How soon Capella rises, and how high you’ll find it, depend on your latitude. The farther north you are, the sooner and higher.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is out of sight in conjunction with the Sun.

Venus, magnitude –3.9, gleams low in the west-southwest as evening twilight fades. It sets around twilight’s end.

Mars and Jupiter (magnitudes +0.5 and –2.5, respectively) rise in late evening and show best in the early-morning sky. Watch for Jupiter to rise in the east-northeast around 10 p.m. daylight-saving time. (The orangy point about a fist at arm’s length to Jupiter’s right or upper right is Aldebaran.) Mars comes up almost two hours after Jupiter now, two fists to its lower left.

Once they’re up, you’ll see that bright Jupiter is shining in Taurus near the Bull’s horntip stars, Beta and Zeta Tauri. This week it stays almost stationary with respect to them. Mars is creeping across central Gemini, between the two stick-figure Twins (which are lying on their sides).

The two planets are highest toward the south around the beginning of dawn, where they shine through thinner, steadier air for the best telescopic views. Jupiter is now a nice 42 arcseconds wide; it will enlarge month by month toward its opposition in December. Mars in a telescope is still a visually disappointing little orange blob, 7.5 arcseconds wide, on its way to a mediocre opposition next January.

Mars here shows its North Polar Cap, dark Mare Sirenum near the South Polar Cloud Hood, and some finer detail. On Jupiter, the North Equatorial Belt (with a bright white cloud outbreak) is slightly darker than the South Equatorial Belt, at least on this side of the planet.

Saturn, magnitude +0.7 in Aquarius, is a couple weeks past opposition. As the stars come out it’s already nicely up in the southeast. It’s two fists lower right of the Great Square of Pegasus, which balances on one corner after dark. This week the Square’s upper-right edge points exactly at Saturn. By 10 or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time, Saturn is about as high toward the south as it will get.

Uranus (magnitude 5.6, in western Taurus) is 24° west of Jupiter, so it’s well up by late evening. You’ll need a good finder chart to identify it among surrounding faint stars.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.8, near the Circlet of Pisces) is 14° east of Saturn. Again you’ll need a proper finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows all stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. It’s currently out of print. The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to mag 9.75). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 10 volumes as it slowly works forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s only up to F.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770

No comments! Be the first commenter?