[ad_1]

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 20

■ Are you spotting Venus yet low in the afterglow of sunset? Is Spica, nearby, already gone for you even with optical aid? See the scene below.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 21

■ The waning gibbous Moon rises in mid-evening, around 9 p.m. daylight saving time. Once the Moon is well up, notice the Pleiades just a few degrees to its lower left. The Moon creeps closer to them all through the night. It skims the cluster’s southern edge around dawn, depending on your location.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 22

■ Goodbye to summer — at last! Today is equinox day. Earth passes the September equinox point in its orbit at 8:44 a.m. EDT (12:44 UT). This is when the Sun, in its six-month journey south, crosses the celestial equator — and equivalently, Earth’s equator. Fall officially begins in the Northern Hemisphere, spring in the Southern Hemisphere.

Coincidentally, as if to mark this transition every year, Deneb has been slowly taking over from brighter Vega as the zenith star at nightfall.

MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 23

■ The almost last-quarter Moon rises around 10 or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time. It’ll be exactly last quarter at 2:50 p.m. EDT tomorrow the 24th, halfway between the early-morning hours of tonight and tomorrow night. In the early-morning hours of tonight, the Moon forms a not-quite rectangle with Jupiter and the two fainter stars Beta and Zeta Tauri, as shown below.

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 24

■ The wide W pattern of Cassiopeia is tilting up high in the northeast after dark. Find the W’s third segment counting down from the top. Continue it down by almost twice the segment’s length, and there will be an enhanced little spot of the Milky Way’s glow if you have a dark enough sky. Binoculars will show it to be the Perseus Double Cluster — even through a fair amount of light pollution.

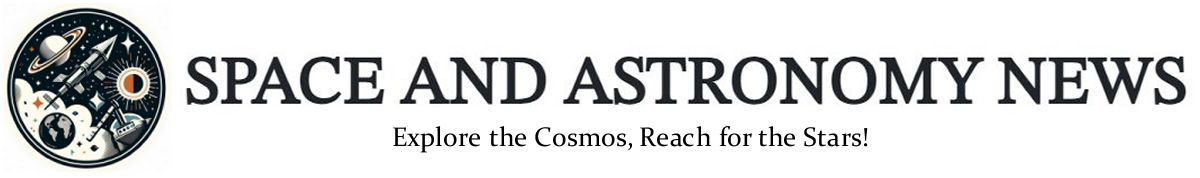

■ The waning Moon accompanies Mars before and during Saturday’s dawn, as shown above.

WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25

■ The Great Square of Pegasus is high in the east after dark, balancing on one corner.

Running lower left from the Great Square’s left corner is a big line of three 2nd-magnitude stars. These mark the head, backbone and leg of the constellation Andromeda. (The line of three includes the Square’s corner, her head.) Upper left from the foot of this line, you’ll find the Cassiopeia W tilting up.

■ Look east before dawn Thursday morning the 26th, and you’ll find the waning Moon nearly aligned with Castor and Pollux as shown above.

Looking wider, the Moon marks the lower left end of a long, ragged string that includes Mars, Jupiter, and Aldebaran.

And, as Gary Seronik writes in the September Sky & Telescope, “You can picture the Moon and Pollux as holding down the upper-left corner of an isosceles [two-equal-sides] triangle with Mars and, below them, Procyon.” Off to the right of this triangle will be Orion. Below Orion shines searing Sirius.

THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 26

■ Arcturus shines in the west these evenings after twilight fades out. Capella, equally bright, is barely rising in the north-northeast (depending on your latitude. The farther north you are the higher it will be.) Both stars are magnitude 0.

Later in the evening, sometime around 9 p.m. depending on your location, Arcturus and Capella shine at the same height in their respective compass directions. When will this happen? That depends on both your latitude and longitude.

When it does, turn around and look low in the south-southeast. There will be 1st-magnitude Fomalhaut at about the same height too — exactly so if you’re at latitude 43° north (Boston, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Boise, Eugene). Seen from south of that latitude, Fomalhaut will appear higher than Capella and Arcturus are. Seen from north of there, it will be lower.

FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 27

■ This is the time of year when the rich Cygnus Milky Way crosses the zenith about an hour after full dark. (for skywatchers at mid-northern latitudes). The Milky Way extends straight up from the south-southwest horizon, passed overhead, and runs straight down to the north-northeast.

SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 28

■ Cygnus itself floats, swan-like, nearly straight overhead these evenings. Its brightest stars form the big Northern Cross.

When you face southwest and crane your head way, way up, the cross appears to stand upright. It’s about two fists at arm’s length tall, with Deneb as its top. Or to put it another way, when you face southwest the Swan appears to be diving straight down.

■ Step out before or during early dawn Sunday morning the 29th, and look for 1st-magnitude Regulus 2° or 3° to the right of the waning crescent Moon as shown below.

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 29

■ Face south and look high these evenings after dark. The brightest star there is Altair, the southernmost point of the Summer Triangle. The other two are Deneb and Vega more nearly overhead. A marker for Altair is always its little neighbor Tarazed (Gamma Aquilae), currently a finger-width at arm’s length to Altair’s upper right.

■ Barely a fist at arm’s length above Altair, high look for the faint little constellation Sagitta, the Arrow. The Arrow points to the upper left. If your light pollution hides it, try binoculars. It’s 4½° long from tailfeathers to tip, easily fitting into the field of view of most binoculars.

Now imagine rotating the Arrow around its tip a third of a turn counterclockwise. Its middle star would now rest just barely (0.4°) below M27, the big Dumbbell Nebula.

At a total magnitude of 7½, the Dumbbell is a largish but subtle gray glow nearly 0.1° wide, easily seen in binoculars or a finderscope under a dark sky. In a 4- to 8-inch telescope it’s a rectangle or hourglass. It’s the brightest planetary nebula in the sky if you sum up all its spread-out light. Read all about observing it in Ken Hewitt-White’s Suburban Stargazer column in the September Sky & Telescope, page 55.

The star HD 189733, magnitude 7.7, is a yellow-orange K dwarf 63 light-years away, notable for having a hot-Jupiter exoplanet orbiting it very closely. The nebula is far in the background, about 1,360 light-years away.

The name Dumbbell Nebula was bestowed by John Herschel in 1828. He was referring to the exercise weights we still call dumbbells, but in his day they were sometimes made by connecting two heavy bells top-to-top by a short, thick rod. The bells were missing their clappers; they were dumb bells. A much more recent name for M27, more accurate to modern eyes, is the Applecore Nebula. The earliest use of this name I find in Google Books is from 1997.

This Week’s Planet Roundup

Mercury is out of sight in conjunction with the Sun.

Venus, magnitude –3.9, shines low in evening twilight. Starting 30 or 40 minutes after sunset, look for it gleaming above the west-southwest horizon. It sets before nightfall is complete.

Mars and Jupiter (magnitudes +0.5 and –2.4, respectively) display themselves best in the early-morning sky. Jupiter shines brightly in Taurus near the Bull’s horntip stars, Beta and Zeta Tauri. Mars this week is creeping across central Gemini.

Watch for Jupiter to rise in the east-northeast around 10 or 11 p.m. daylight-saving time. Check for Aldebaran about a fist at arm’s length to Jupiter’s upper right. It remains to Jupiter’s upper right or right through the night.

Mars rises about an hour and a half after Jupiter, to its lower left. By the beginning of dawn the two planets are very high toward the southeast, shining through thinner, steadier air for better telescopic views. Jupiter is now a nice 41 arcseconds wide telescopically, and it will enlarge month by month toward its opposition in December. Mars in a telescope is still a visually disappointing little orange blob, 7.5 arcseconds wide, on its way to a mediocre opposition next January.

On Mars, the upward (northward) pointing dark marking is Syrtis Major. South of the dark complex, the Hellas basin is bright. The North Polar Cap is tilted into view, still large but showing some of its dark collar.

On Jupiter, the North Equatorial Belt on this side of the planet is slightly darker than the South Equatorial Belt.

Saturn, magnitude +0.7 in Aquarius, is just a week or so past opposition. Look for it glowing in the southeast as the stars come out. It’s lower right of the Great Square of Pegasus, which is balancing on one corner. The Square’s upper-right edge points diagonally more or less to Saturn, two fists at arm’s length away.

Saturn climbs higher through the evening. It shines highest in south by 11 or midnight.

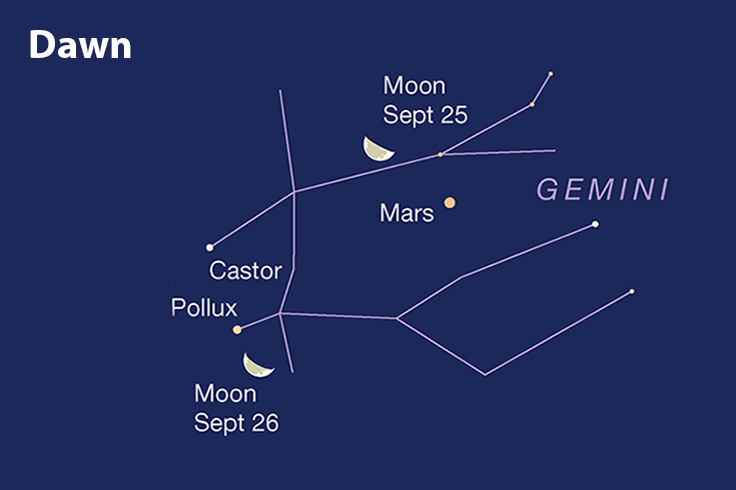

Uranus (magnitude 5.7, in western Taurus) is some 24° XXXX west of Jupiter, and thus it’s well up by late evening. You’ll need a good finder chart to identify it among surrounding faint stars.

Neptune (tougher at magnitude 7.8, near the Circlet of Pisces) is 13° XXXX east of Saturn. Again you’ll need a proper finder chart.

All descriptions that relate to your horizon — including the words up, down, right, and left — are written for the world’s mid-northern latitudes. Descriptions and graphics that also depend on longitude (mainly Moon positions) are for North America.

Eastern Daylight Time (EDT) is Universal Time minus 4 hours. UT is also known as UTC, GMT, or Z time.

Want to become a better astronomer? Learn your way around the constellations. They’re the key to locating everything fainter and deeper to hunt with binoculars or a telescope.

This is an outdoor nature hobby. For a more detailed constellation guide covering the whole evening sky, use the big monthly map in the center of each issue of Sky & Telescope, the essential magazine of astronomy.

Once you get a telescope, to put it to good use you’ll need a much more detailed, large-scale sky atlas (set of charts). The basic standard is the Pocket Sky Atlas (in either the original or Jumbo Edition), which shows all stars to magnitude 7.6.

Next up is the larger and deeper Sky Atlas 2000.0, plotting stars to magnitude 8.5; nearly three times as many. It’s currently out of print. The next up, once you know your way around well, are the even larger Interstellarum atlas (stars to magnitude 9.5) or Uranometria 2000.0 (stars to mag 9.75). And read How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope. It applies just as much to charts on your phone or tablet as to charts on paper.

You’ll also want a good deep-sky guidebook. A beloved old classic is the three-volume Burnham’s Celestial Handbook. An impressive more modern one is the big Night Sky Observer’s Guide set (2+ volumes) by Kepple and Sanner. The pinnacle for total astro-geeks is the Annals of the Deep Sky series, currently at 10 volumes as it slowly works forward through the constellations alphabetically. So far it’s only up to F.

Can computerized telescopes replace charts? Not for beginners I don’t think, and not for scopes on mounts and tripods that are less than top-quality mechanically. Unless, that is, you prefer spending your time getting finicky technology to work rather than learning how to explore the sky. As Terence Dickinson and Alan Dyer say in their Backyard Astronomer’s Guide, “A full appreciation of the universe cannot come without developing the skills to find things in the sky and understanding how the sky works. This knowledge comes only by spending time under the stars with star maps in hand and a curious mind.” Without these, “the sky never becomes a friendly place.”

If you do get a computerized scope, make sure that its drives can be disengaged so you can swing it around and point it readily by hand when you want to, rather than only slowly by the electric motors (which eat batteries).

However, finding faint telescopic objects the old-fashioned way with charts isn’t simple either. Learn the essential tricks at How to Use a Star Chart with a Telescope.

![]() Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

Audio sky tour. Out under the evening sky with your

earbuds in place, listen to Kelly Beatty’s monthly

podcast tour of the naked-eye heavens above. It’s free.

“The dangers of not thinking clearly are much greater now than ever before. It’s not that there’s something new in our way of thinking, it’s that credulous and confused thinking can be much more lethal in ways it was never before.”

— Carl Sagan, 1996

“Facts are stubborn things.”

— John Adams, 1770

[ad_2]

Source link

No comments! Be the first commenter?