Extreme Climate Survey

Science News is collecting reader questions about how to navigate our planet’s changing climate.

What do you want to know about extreme heat and how it can lead to extreme weather events?

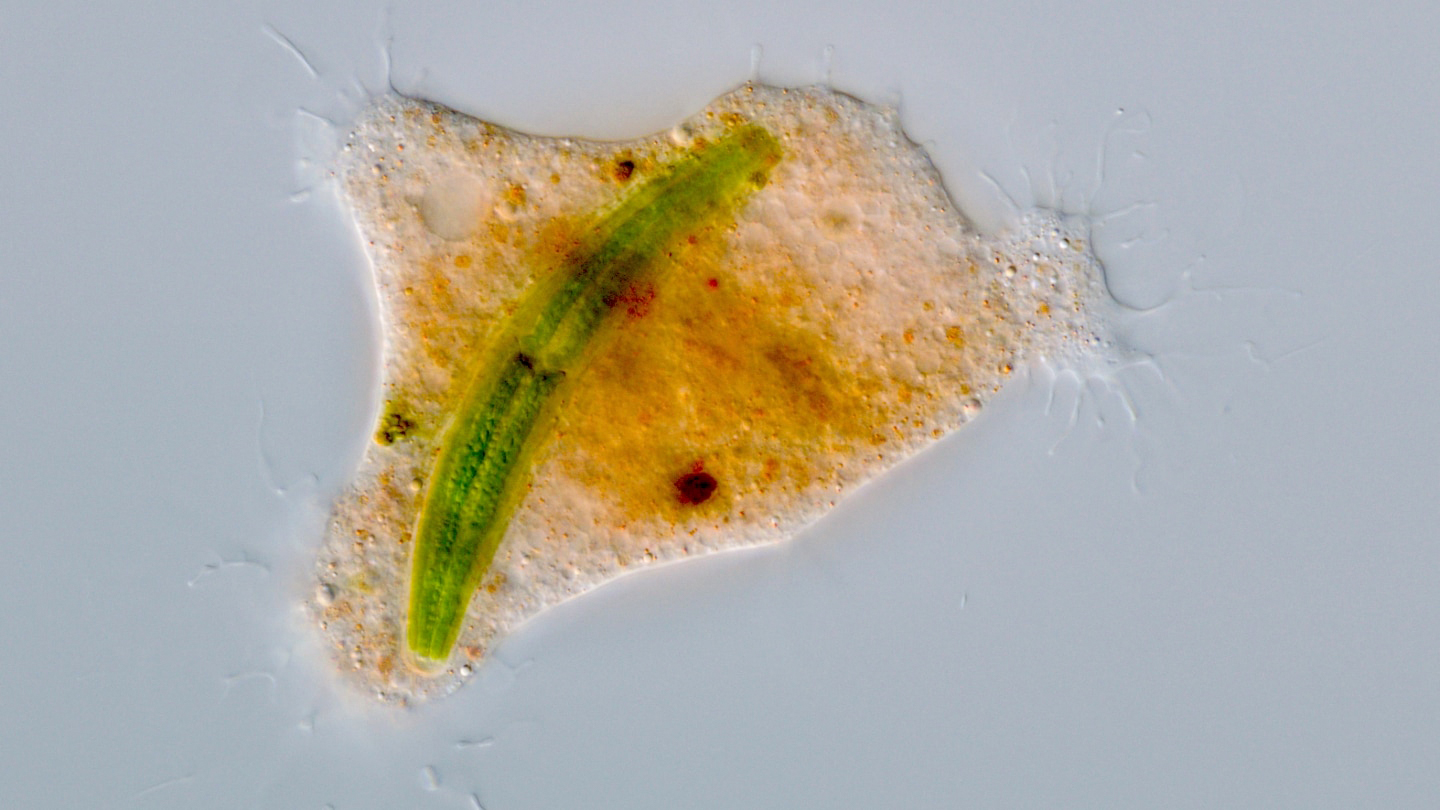

Under the microscope, one water-filled petri dish was teeming with round, reddish, immobile blobs — what vampyrellids look like after feeding. But nearby algae lacked telltale feeding holes.

Time-lapse photography confirmed the amoebas were vampyrellids. But they didn’t feed like other microscopic vampires. The unicellular blobs engulfed and split apart Closterium algae cells, sucking out the insides and tossing the rest.

“We just couldn’t believe it at first,” Suthaus says. “Of course, the question becomes, well, how exactly do [the amoebas] do it?”

Feeding experiments revealed that S. ruptor keeps engulfed algae in a special compartment. Enzymes in this chamber appear to dissolve one side of the prey’s cell wall. The other side is attached to the chamber wall. As the compartment expands, the algae cell swings open like a shelled pistachio. S. ruptor then reaches into itself to scoop up its meal, bundling up and spitting out the empty cell wall.

The odd vampyrellids belong to a previously undescribed genus and species, a genetic analysis suggests. The genus name Strigomyxa, which derives from the ancient Greek words for owl and mucus or slime, is a nod to the microbe’s owllike regurgitation behavior.

“When you see similar pellet-casting in a lot of other organisms, they have multiple cells that fulfill multiple functions. And this is a single cell doing this type of mechanistic action,” Suthaus says. “It tells us about the ingenuity of evolution.”

*

Source link

No comments! Be the first commenter?