*

NASA

Saturn passed opposition on September 8th and is now well placed in the southeastern sky at nightfall in Aquarius. I can still recall the first time I found the planet from my front yard in the winter of 1965. It was situated in almost the same location you’ll find it tonight, a few degrees northwest of the “crooked fingertip” asterism formed by the three Psis — Psi1 (ψ1), Psi2 (ψ2), and Psi3 (ψ3) Aquarii. Wish me happy birthday — I’m two Saturn-years old!

Stellarium

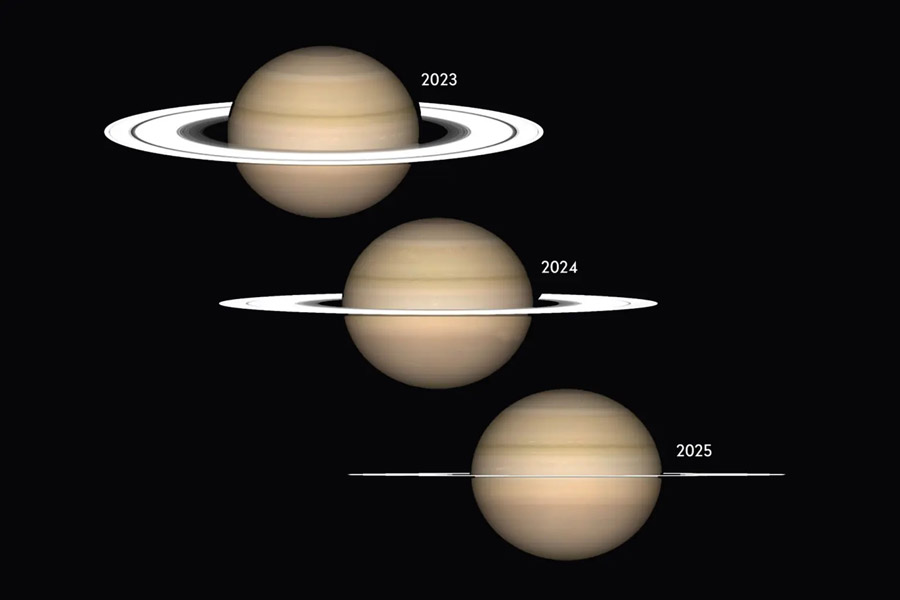

This year and next are special years for the sixth planet because observers will have several opportunities to view the rings nearly edge on, something that only happens about once every 15 years when the Earth crosses through their orbital plane. Unfortunately, during the current apparition, edgewise presentation occurs on March 23, 2025, only 11 days after solar conjunction. Steeped in the solar glow the planet will be unobservable.

Stellarium

Come mid-April we’ll get our first glimpse of the south face when the ring plane tips open a hair to –1.5°. Even then, Northern Hemisphere observers will have to dig into twilight to view the planet. The rings reach their maximum southern tilt of –3.8° in early July before narrowing again to a minimum of –0.5° in mid-November. By early December the flip-flopping ends and the ring plane steadily opens to a maximum of 27° in 2033. The next ring plane crossing we’ll see in a dark sky occurs in October 2038. Holy quasars, that’s a long wait.

Stellarium

With the planet’s current tiny tilt, the moons, which normally cluster about the planet, are strung out in a more linearly fashion, making them easier to spot when they reach greatest elongation. Flattened rings also reduce the planet’s overall brightness, which further helps in picking out the fainter moons. Like the rings, the major moons orbit in the equatorial plane, which means that as Earth approaches that plane, we can watch them eclipse and occult one another in what are called mutual events. Indeed, the 2024–2026 mutual event season is already underway.

Stellarium

Similar events occur when we pass through Jupiter’s orbital plane, but its moons are large enough to discern as disks while all of Saturn’s satellites — with the exception of Titan (diameter 0.8″) — are only a whisper of an arcsecond across. Many of the upcoming events occur among the fainter moons close to the planet’s glare and will prove challenging. But as the ring plane flattens out, events become more frequent and also involve the larger moons farther out from the planet, making them easier to see.

Stellarium

The Institute of Celestial Mechanics and Computation of Ephemerides (IMCCE) maintains a complete list of Saturn satellite events with a clear explanation on how to read and use the data. Check it out and make a note of significant occultations and eclipses visible from your observing site. One of the key variables is the impact factor — the closer it is to “0” the better. Zero indicates a central passage of the moon through the shadow or across the disk of another moon. Grazing events are equal to “1.” To interpret the event shorthand under the Type column you’ll need to know each moon’s number designation. They are: Mimas (1), Enceladus (2), Tethys (3), Dione (4), Rhea (5), Titan (6), Hyperion (7), and Iapetus (8). For example, when you read “3E2,” it means Tethys will eclipse Enceladus, while “3O4” indicates that Tethys will occult Dione. To know just where to look beforehand I suggest you simulate each local event using Stellarium or similar free stargazing software. The next event visible from the Americas will be a partial eclipse of Tethys by Enceladus on October 1st starting at 10:58 p.m. EDT and ending at 11:07 p.m.

Stellarium

There are also lots of “close calls” when two or more moons make a tight pair or triplet for a brief period of time. These are fun to watch because you can easily and quickly detect their orbital motion, while prying moons apart at various magnifications makes for good sport. To help in identifying Saturn’s satellites it’s good to know their magnitudes. Titan is the brightest at magnitude 8.4, followed by Rhea (9.7), Tethys (10.2), Dione (10.4), Iapetus (variable but bright at ~11 in late September), Enceladus (11.7), Mimas (12.9), and Hyperion (14.3). While Jupiter is often toted out as a model of the solar system in miniature, Saturn fulfills the same role with aplomb.

No comments! Be the first commenter?