[ad_1]

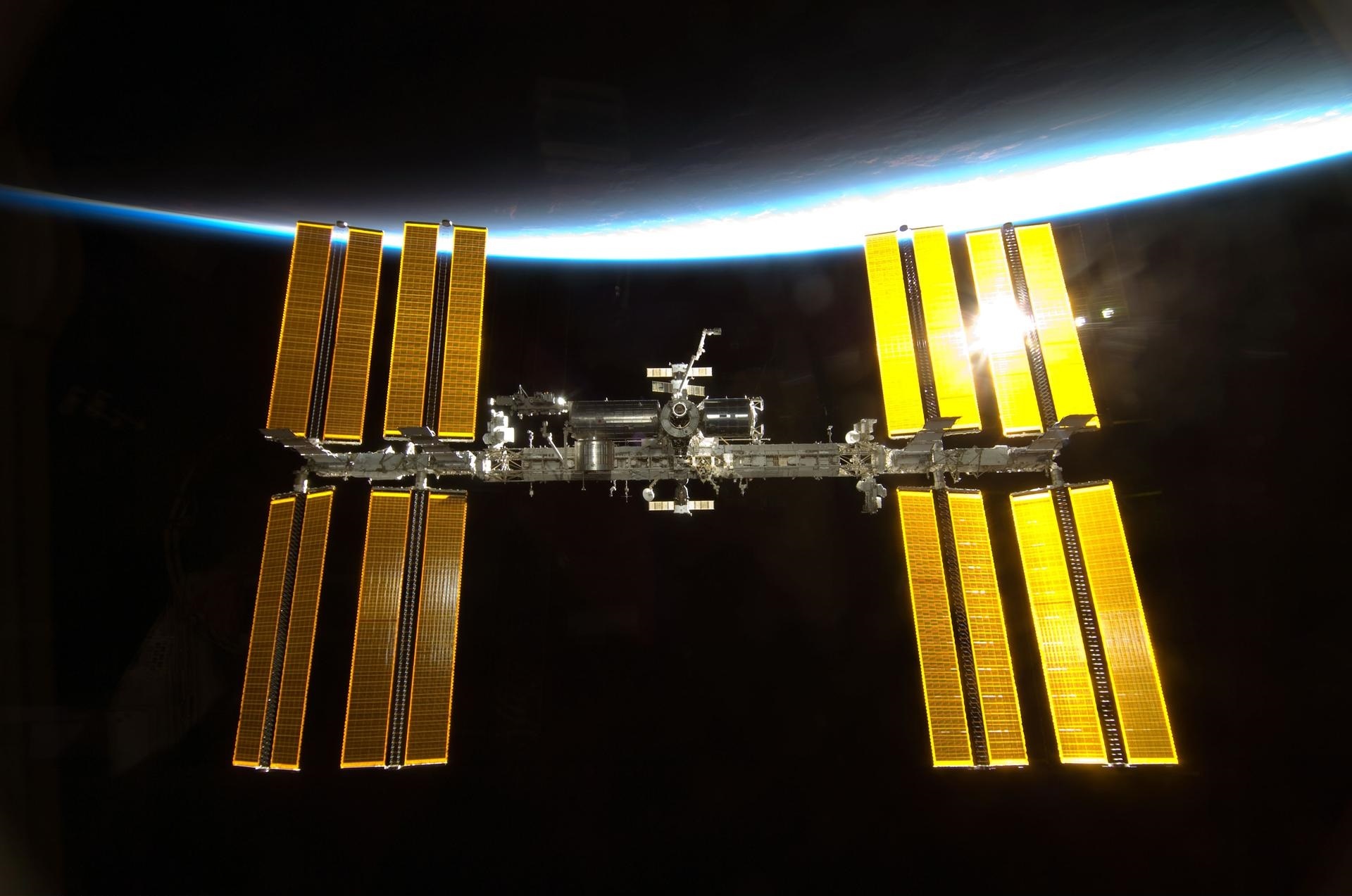

The outer Solar System has been a treasure trove of discoveries in recent decades. Using ground-based telescopes, astronomers have identified eight large bodies since 2002 – Quouar, Sedna, Orcus, Haumea, Salacia, Eris, Makemake, and Gonggang. These discoveries led to the “Great Planet Debate” and the designation “dwarf planet,” an issue that remains contentious today. On December 21st, 2018, the New Horizons mission made history when it became the first spacecraft to rendezvous with a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) named Arrokoth – the Powhatan/Algonquin word for “sky.”

Since 2006, the Subaru Telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii has been observing the outer Solar System to search for other KBOs the New Horizons mission could study someday. In that time, these observations have led to the discovery of 263 KBOs within the traditionally accepted boundaries of the Kuiper Belt. However, in a recent study, an international team of astronomers identified 11 new KBOs beyond the edge of what was thought to be the outer boundary of the Kuiper Belt. This discovery has profound implications for our understanding of the structure and evolution of the Solar System.

The research team was led by Wesley C. Fraser, a Plaskett Fellow and a Professor of Astronomy at the University of Victoria (UVic) and the Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre. He was joined by colleagues from UVic, the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), NOIRLab, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS), the Instituto de Astrofisica de Andalucia, the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and many other institutes and universities. The paper that describes their findings recently appeared in the Planetary Science Journal.

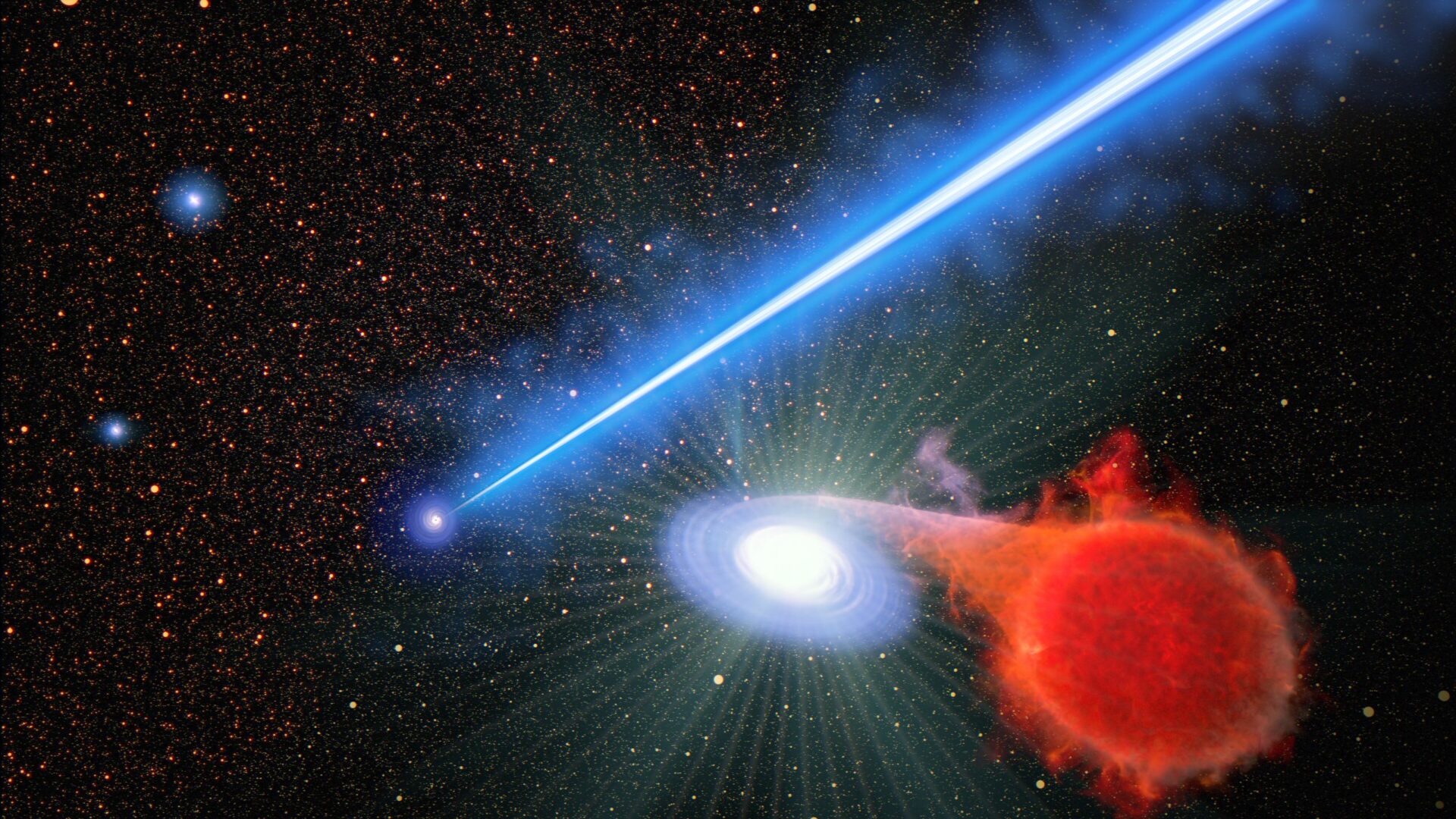

In recent years, mounting evidence has been provided that objects exist beyond the edge of the Kuiper Belt. However, this study is the first to provide clear evidence of a large number of objects in a relatively small search area that cannot be attributed to false positives. Moreover, these KBOs appear to represent a new class of objects that orbit in a ring separated from the known Kuiper Belt by a gap where very few objects exist. This type of structure has been observed around many young planetary systems observed by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) array.

This suggests that the Solar System has more in common with extrasolar systems than previously thought, which could have implications for astrobiology—the search for extraterrestrial life in the Universe. Dr. Fraser, who is also a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission science team, explained in a NOAJ press release:

“Our Solar System’s Kuiper Belt long appeared to be very small in comparison with many other planetary systems, but our results suggest that idea might just have arisen due to an observational bias. So maybe, if this result is confirmed, our Kuiper Belt isn’t all that small and unusual after all compared to those around other stars.”

As any astrobiologist knows, the search for life is a major challenge because of our limited perspective. To date, we know of only one planet where life emerged and evolved (i.e., Earth), making it difficult to understand what conditions life can arise from. As such, scientists are eager to identify what sets our Solar System apart from others to constrain the prerequisites for life. Discovering that the Kuiper Belt may be larger than previously thought eliminates the idea that larger belts are an impediment to the emergence of life in extrasolar systems (possibly because they constitute a larger population of potential comets).

“If this is confirmed, it would be a major discovery,” said study co-author Dr. Fumi Yoshida of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health and the Planetary Exploration Research Center. “The primordial solar nebula was much larger than previously thought, and this may have implications for studying the planet formation process in our Solar System.”

“This is a groundbreaking discovery revealing something unexpected, new, and exciting in the distant reaches of the Solar System; this discovery probably would not have been possible without the world-class capabilities of Subaru Telescope,” added New Horizons mission Principal Investigator Dr. Alan Stern.

These results indicate that more discoveries await beyond the traditionally recognized edge of the Kuiper Belt, which was thought to be a cold, empty end of space. They also entice astronomers to conduct follow-up studies to confirm these results and identify additional families of objects. Last but certainly not least, they offer a tantalizing clue as to what objects the New Horizons mission may be able to study someday.

Further Reading: NAOJ, Planetary Science Journal

[ad_2]

Source link

No comments! Be the first commenter?