Americans are famously fond of their guns. So it should come as no surprise that a team of NASA scientists has devised a way to “shoot” a modified type of sensor into the soil of an otherworldly body and determine what it is made out of. That is precisely what Sang Choi and Robert Moses from NASA’s Langley Research Center did, though their bullets are miniaturized spectrometers rather than hollow metal casings.

First, let’s look at the miniaturized spectrometers. Spectrometers have been a workhorse of space exploration for decades. They analyze everything from the surface of Enceladus to stars. However, they almost all use a type of spectroscopy known as Fraunhofer diffraction. Drs. Choi and Moses decided to use a different physical phenomenon in their invention, known as Fresnel’s diffraction.

In Fresnel diffraction, a spectral graph becomes very clear at much smaller distances than those created by Fraunhofer diffraction. Since the necessary distance between a “grating” and the sensor required by a spectrometer using Fraunhofer diffraction is one of the system’s design constraints, most spectrometers in use today are prohibitively large.

Fresnel diffraction, however, allows for the creation of much smaller spectrometers. In the case of Dr. Choi and Moses’s invention, all of the necessary power, signaling, and analysis electronics can fit into a small cylindrical tube only slightly larger than a traditional bullet.

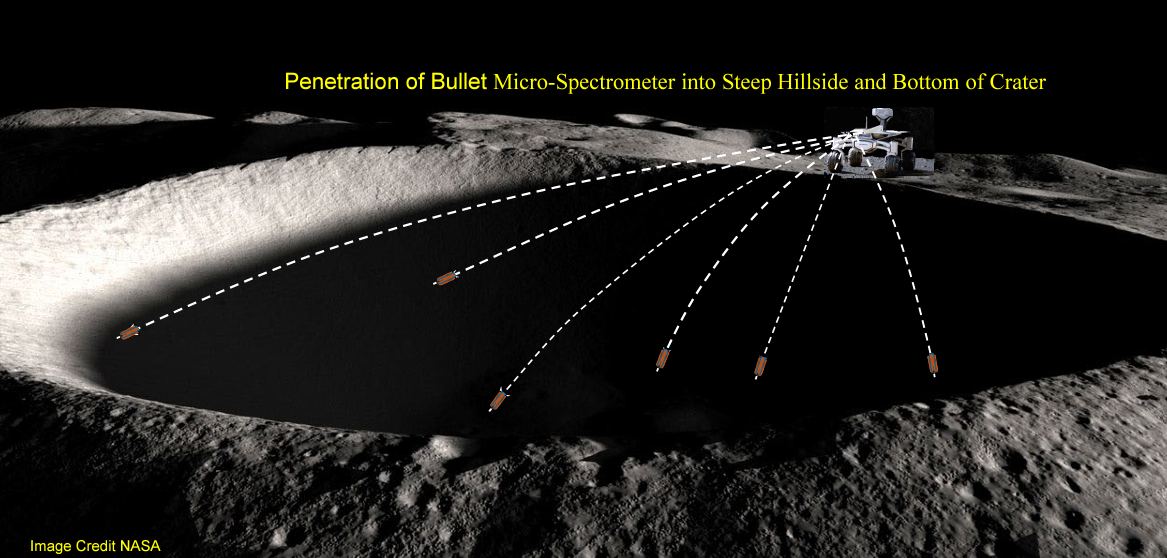

That was likely where the idea for shooting these sensors into the ground came from. If the “micro-spectrometers” were surrounded by regolith, whether the Moon, an asteroid’s, or Mars’, it would allow quick analysis of the composition of the soil wherever it is embedded. Since these sensors are easily deployed, if multiple of them were spread throughout a lunar crater, a single astronaut (or rover) could characterize the soil makeup of an entire area without hand-digging a space for each sample area.

This is where the “gun” comes in—a rover, or even an astronaut, could be fitted with a tube that “fires” the cylindrical micro-spectrometer into the ground, embedding it where it can do the best science. A single rover or astronaut could then distribute enough of these to collect data on an entire area, such as the permanently shadowed regions of a lunar crater.

Credit – Choi and Moses

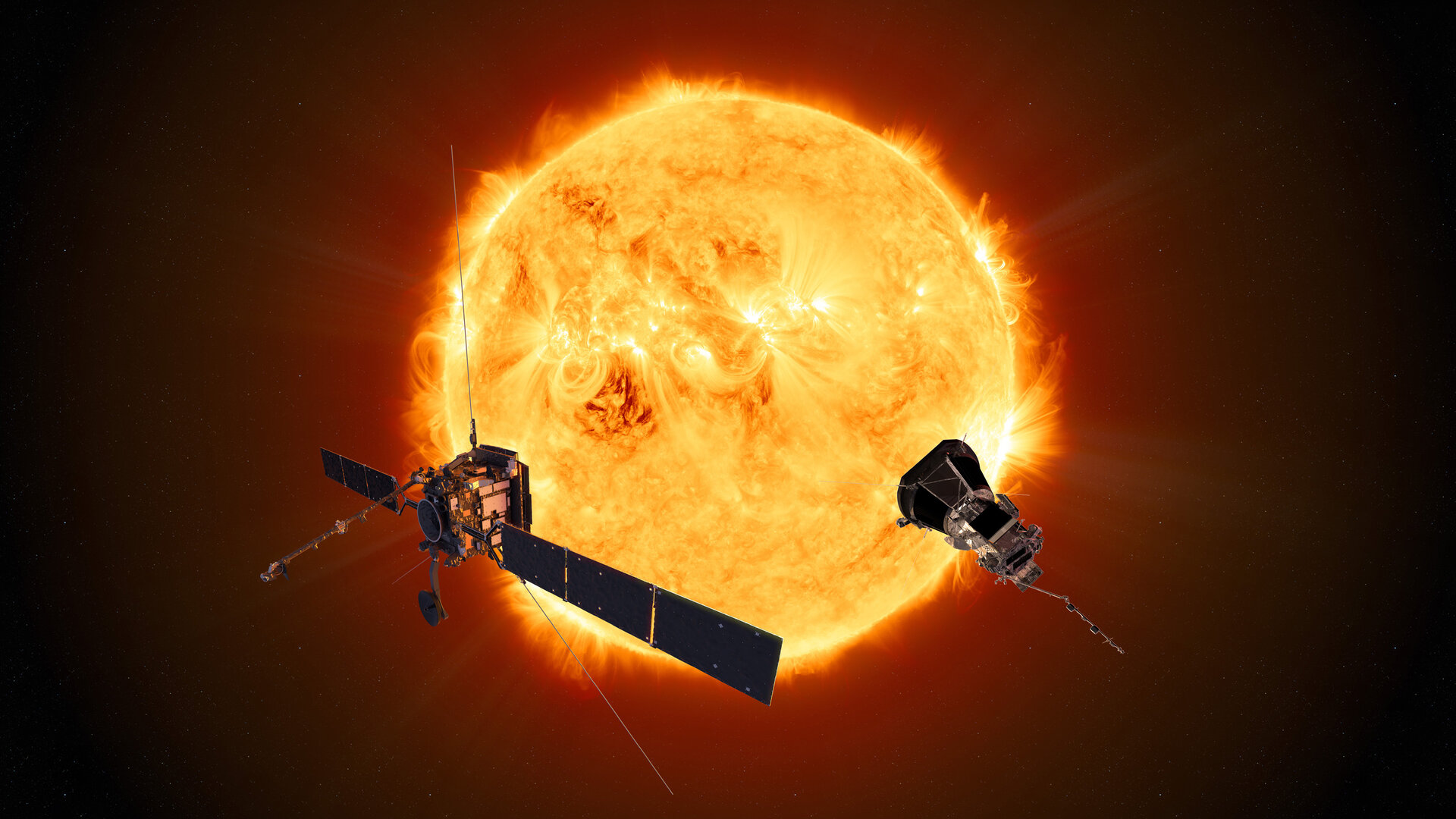

Such a system could also be used on asteroids from an orbiter or even Mars. It could use telemetry back to a central connection point—potentially also carried by the astronaut or rover. Unfortunately, at least in the current iteration, it couldn’t be reused, though that could change in new designs.

This invention, which NASA has patented, could also be used on Earth if a mining or petroleum company wants to quickly sample an area’s geological makeup. But it is also useful in space—so much so that we might someday find astronauts shooting what look to be bullets but are actually miniaturized sensors directly into the ground.

Learn More:

Sang H Choi – Lunar, Mars, and Asteroid Exploration for Space Resources

Choi & Moses – Micro-Spectrometer for Resource Mapping in Extreme Environments

UT – The Darkest Parts of the Moon are Revealed with NASA’s New Camera

UT – Absorption Spectroscopy

Lead Image:

Depiction of the “bullets” being deployed in a lunar crater.

Credit – NASA

No comments! Be the first commenter?