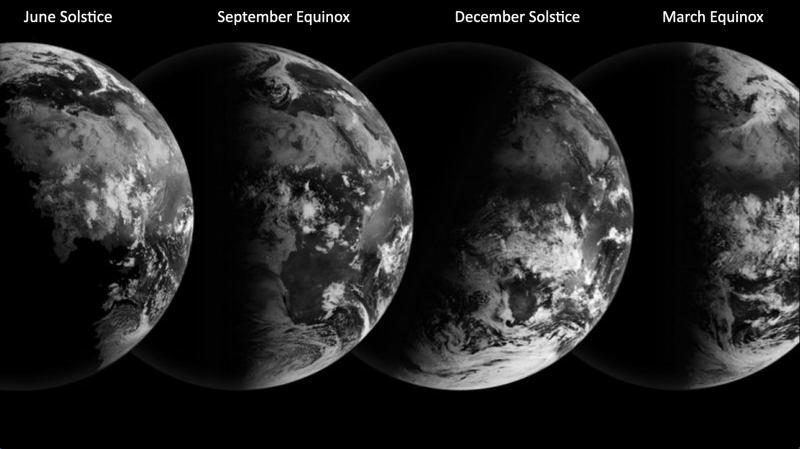

More day than night

The September equinox will come on Sunday, September 22, 2024, at 12:44 UTC (7:44 a.m. CDT on September 22 for central North America). It’s the Northern Hemisphere’s autumn equinox and Southern Hemisphere’s spring equinox. You sometimes hear it said that, at the equinoxes, everyone receives about equal daylight and darkness. But there’s really more daylight than darkness at the equinox, eight more minutes or so at mid-temperate latitudes. Two factors explain why we have more than 12 hours of daylight on this day of supposedly equal day and night. They are:

1. The sun is a disk, not a point.

2. Atmospheric refraction.

Read more about the September 2024 equinox: All you need to know

The sun is a disk, not a point

Watch any sunset, and you know the sun appears in Earth’s sky as a disk.

It’s not point-like, as stars are, and yet – by definition – most almanacs regard sunrise as when the leading edge of the sun first touches the eastern horizon. They define sunset as when the sun’s trailing edge finally touches the western horizon.

This in itself provides an extra 2 1/2 to 3 minutes of daylight at mid-temperate latitudes.

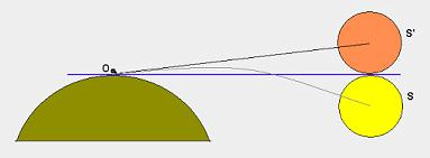

Atmospheric refraction

The Earth’s atmosphere acts like a lens or prism, uplifting the sun about 0.5 degrees from its true geometrical position whenever the sun nears the horizon. Coincidentally, the sun’s angular diameter spans about 0.5 degrees, as well.

In other words, when you see the sun on the horizon, it’s actually just below the horizon geometrically.

What does atmospheric refraction mean for the length of daylight? It advances the sunrise and delays the sunset, adding nearly another six minutes of daylight at mid-temperate latitudes. Hence, more daylight than night at the equinox.

Astronomical almanacs usually don’t give sunrise or sunset times to the second. That’s because atmospheric refraction varies somewhat, depending on air temperature, humidity and barometric pressure. Lower temperature, higher humidity and higher barometric pressure all increase atmospheric refraction.

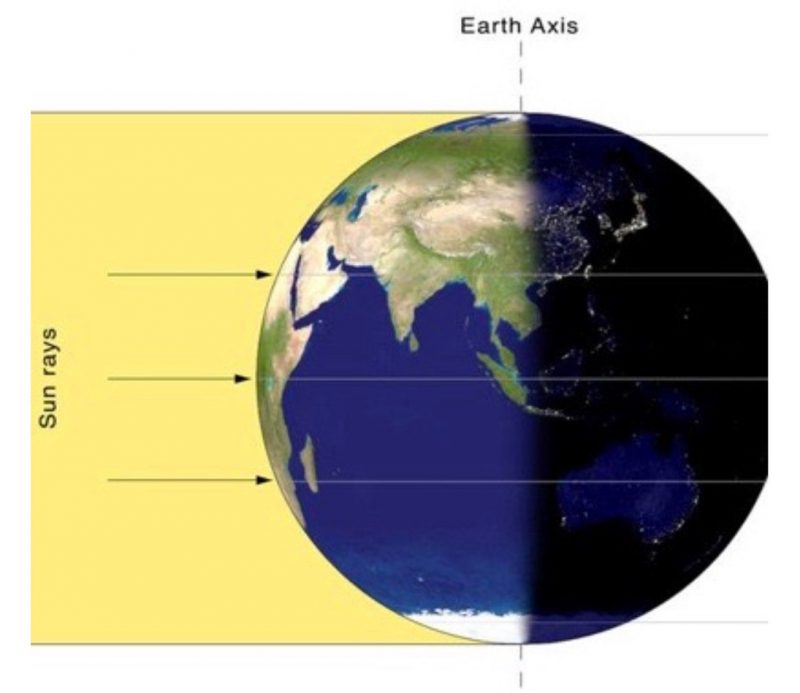

On the day of the equinox, the center of the sun would set about 12 hours after rising – given a level horizon, as at sea, and no atmospheric refraction.

Are day and night equal?

So, no, day and night are not exactly equal at the equinox.

And here’s a new word for you, equilux. The word is used to describe the day on which day and night are equal. The equilux happens a few to several days after the autumn equinox, and a few to several days before the spring equinox.

Much as earliest sunrises and latest sunsets vary with latitude, so the exact date of an equilux varies with latitude. That’s in contrast to the equinox itself, which is a whole-Earth event, happening at the same instant worldwide. At and near the equator, there is no equilux whatsoever, because the daylight period is over 12 hours long every day of the year.

Visit timeanddate.com for the approximate date of equal day and night at your latitude

Bottom line: There’s slightly more day than night on the day of an equinox. That’s because the sun is a disk, not a point of light, and because Earth’s atmosphere refracts (bends) sunlight.

No comments! Be the first commenter?