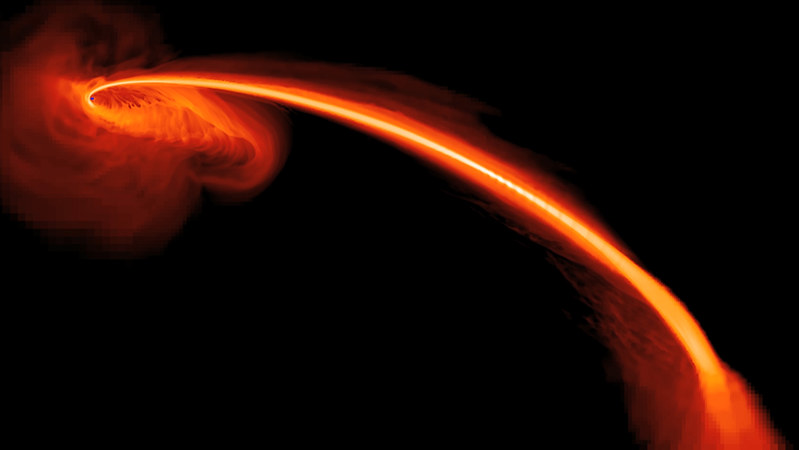

NASA / S. Gezari (The Johns Hopkins University) / J. Guillochon (University of California, Santa Cruz)

When a star ventures too close to a supermassive black hole, the extreme gravitational field pulls on the star, shredding it to pieces. Stellar gas stretches out like taffy before some of it enters the maw, the remainder tossed away like yesterday’s leftovers.

But some stars survive, at least for a while. Their glancing trajectory gives the black hole only a passing chance at consuming them; then they return for a second go-round, and a third. These suckers for punishment can teach astronomers a lot about the physics of star-shredding. Astronomers think a particular tidal disruption event, dubbed AT2018fyk, is one of these stars that’s returning to its black hole companion again and again.

The event was first spotted in 2018 as a flare of light by the global array of telescopes known as All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN). Additional observations from a host of space telescopes of ultraviolet emission and X-rays soon followed. Coming from 800 million light-years away, the flare lasted more than year before it ended as dramatically as it started. Then, after two years of darkness, it blazed back to life.

Black hole–shredded stars are rare: The supermassive black hole at the center of any given galaxy will only tear into a star every 10,000 to 100,000 years. Repeating events such as this one are even rarer — astronomers have only detected a handful so far — making it all the more valuable.

Dheeraj Pasham (MIT) and colleagues present a possible scenario explaining the observations obtained so far in the August 20th Astrophysical Journal. They suggest a massive star entered an elongated orbit around the black hole in 2018, swinging by for a close pass before soaring away again on its long loop. That first passage resulted in the first, year-long brightening, as the black hole’s gravity tore off the star’s outer layers and sent them spiraling into the pit of spacetime.

But the star has its own gravity, so there’s a region of space around it that’s largely empty of stripped-out gas. By the time the star passed closely by the black hole again, about three years later, that empty region enveloped the black hole. Feeding shut off, and so did the brightness.

The black hole’s gravity, relentless as ever, still pulled gas off the star as it whizzed by. About 1½ to 2 years later, that material fell back into the black hole. Once again, it heated up and emitted radiation, relighting the candle so to speak, before a third close passage of the star snuffed it out again.

“A repeating partial tidal disruption event is exciting because you can actually witness the repeated passages of the bound star with the massive black hole, and from the resulting accretion events, determine the physical parameters of the star’s orbit and even its internal structure,” says Suvi Gezari (Space Telescope Science Institute), who wasn’t involved in this study.

Illustration: NASA / CXC / M. Weiss

Even during the current dark period, astronomers are on the lookout for a predicted characteristic of a partially shredded star: It ought to have two tails. One tail of gaseous stellar material extends toward the black hole while another tail points away. Observations taken right now, while the black hole isn’t feeding, should reveal a faint X-ray glow from the second tail of escaping material. Pasham says the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Neutron Star Interior Explorer (NICER), XMM-Newton, and the Chandra X-ray Observatory are all keeping their eyes open for this emission.

The scenario also makes a specific prediction on when the next grab for stellar gas will come: in early 2025. How many more rounds we’ll get to see after that depends on what kind of star it is.

“Two things can happen: The star can either get fully disrupted in one of the future encounters, or it can also receive an outward kick and become unbound to the supermassive black hole,” Pasham says. Future observations will tell whether this star awaits destruction or escape.